By: Chelsea Morin

On Thursday, June 26, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously on a constitutional matter that had never before seen the steps of the Supreme Court. In National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning, the Court found that President Obama had overstepped his executive power in 2012 when he made three appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) without Senate approval.

Obama attempted to make these appointments through the so-called “Recess Appointments Clause” under Article II, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, which states “[t]he President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.” When the President took action, the Senate was in the midst of conducting “pro forma sessions” during which it would convene every three days or so in order to meet its constitutional obligation. While the President claimed that the Senate had agreed to gavel in pro forma only as a tactic to prevent him from filling in the NLRB seats, the Supreme Court refused to accept this argument, holding that pro forma sessions do not count as periods of recess. The Court highlighted the deference given to the Senate, because “under its own rules, it retains the capacity to transact Senate business,” regardless of the functionality of the session.

In the beginning of the Canning opinion, the Court made it clear that the Recess Appointments Clause is only a “subsidiary, not a primary method for appointing officers of the United States.” The general mode of appointments is found in the Appointments Clause of Article II, Section 2, Clause 2, which makes the intended separation of powers between the executive and legislative branches clear, only allowing Presidential nominations “by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate.”The most important point that the Court emphasized was that if presidents were allowed to utilize the Recess Appointments Clause in minor “intra-session” breaks, it would be inconsistent with the checks and balance system that the Framers intentionally put in place.

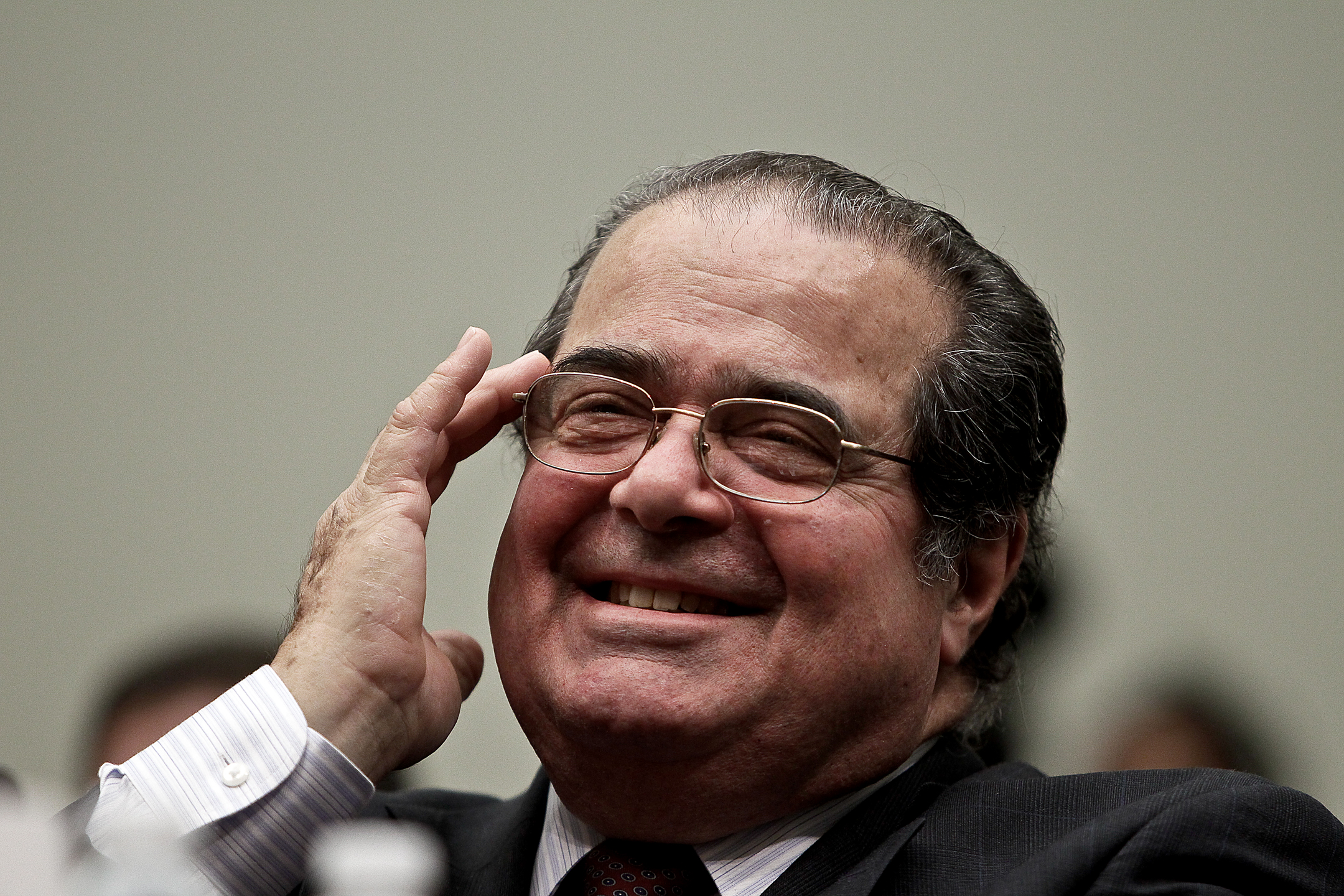

So, what constitutes “the Recess” for purposes of this Clause? While the decision was unanimous, on this point, the Court’s reasoning was divided 5-4. Justice Breyer led liberal thinkers, accompanied by renowned swing-voter, Justice Kennedy, while Justice Scalia wrote a heated concurring opinion joined by his fellow conservative Justices.

The liberal majority interpreted the Clause more broadly due to its silence on what length of time qualifies as “the Recess.” Breyer made it clear that he thought the Framers omitted a formula for determining recess qualifications because “they did not foresee the need for one” due to the lengthy breaks between Senate intra-sessions and reduction of those between Senate inter-sessions. The Court determined that a recess of 10 days qualifies under the text for two reasons: first, because history shows there has not been a recess appointment for a break less than 10 days; secondly, it is presumptively too short to require the consent of the House.

Conservatives were disgruntled by the majority’s opinion, as evidenced by Scalia’s statement that “[t]he Court’s decision transforms the recess-appointment power from a tool carefully designed to fill a narrow and specific need into a weapon to be wielded by future Presidents against future Senates.” Maybe he’s on to something. The Conservative Justices took a formalistic approach in their concurring opinion, asserting that “recess” should mean a time when the Senate is unavailable to participate in the appointments process, during inter-session recesses. The Court of Appeals utilized the same line of reasoning in its decision, stating that the Clause served only as a substitute or a stop-gap “when intersession recesses were regularly six to nine months and senators did not have the luxury of catching the next flight to Washington.”

It seems as though the latter reasoning is more in tune with what the Framers had in mind when constructing the second Appointments Clause. According to Federalist No. 67, the Recess Appointments Clause initially served as “nothing more than a supplement to the [Appointments Clause] for the purpose of establishing an auxiliary method of appointment, in cases to which the general method was inadequate.” Because the power of appointments is a joint power, shared by the President and the Senate, this illustrates that Framers could not have intended the auxiliary clause to serve as a back-door to allow an administration to make appointments and avoid the additional check on powers, the backbone of our Nation’s political system. Ultimately, the true purpose behind this auxiliary method of appointments was to avoid government paralysis. So, it seems as though Justice Scalia’s statement was right, that “the recess appointments will remain a powerful weapon in the President’s arsenal,” which is, indeed, an anachronism.

What impact will this ruling have on the current inner-workings of the Senate? The short answer: not much. Last November, Senate Democrats changed procedural rules to make it more difficult for Senate Republicans to block Obama’s appointees. Democrats exercised a “nuclear option” which stripped the Republican minority of the ability to use filibusters to block presidential nominees who had fewer than 60 votes, allowing the majority to more easily confirm presidential nominations. Nonetheless, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, along with 44 Senate Republicans filed an amicus curiae brief for Noel Canning, pushing for the decision that was released last Thursday. Republicans, therefore, are pleased with the NLRB decision. House Speaker John Boehner declared that it was a “psychological boost” while McConnell victoriously announced that it was a “clear rebuke to the President’s brazen power grab.” While this ruling will have a minimal effect on the current Senate, according to Politico, “[t]he Supreme Court’s decision to rein in the recess appointment power could become more significant if Democrats lose control of the Senate in this fall’s elections” because “it would restore Republicans’ ability to block confirmation of Obama nominees.”

Although the Court deemed that the President’s NLRB appointments were unconstitutional, the Court ultimately limited the Senate’s check on executive power when it held that a 10 day intra-session qualifies as “the Recess” for purposes of the Recess Appointments Clause. The decision blurred the lines between the executive and legislative branches, maneuvering around the Framers’ original structure that ensured for separation of powers.