By: Amelia Wong and Ashli Weiss*

On March 19, 2013, the United States Supreme Court decided that the “first sale” doctrine applies to copies of a copyrighted work made abroad in its Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley and Sons Inc. opinion. This holding allows a person to buy authentic luxury goods made abroad and ship them back to the United States to resell. This article briefly discusses the case law history of the “first sale” doctrine for luxury goods, effects of the Kirtsaeng decision, and proposes a solution to deter adverse results on the luxury goods industry.

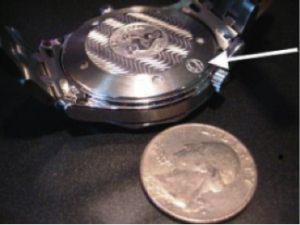

The question of whether the “first sale” doctrine applies to a luxury good was addressed in 2010 by Omega SA v. Costco Wholesale Corporation. In Costco Wholesale, the Supreme Court remained split on the applicability of the first sale doctrine to imported luxury goods. At issue was whether Costco could buy Omega watches abroad from a middleman and sell the watches at a substantially lower price without Omega’s authorization in the U.S. Omega claimed that Costco infringed on Omega’s copyrighted globe on the back of each Omega watch and violated Omega’s right to distribute under the Copyright Act. The Court found Costco liable for infringement in that case, but now, with the decision from Kirtsaeng, the decision would have been in Costco’s favor.

The Kirtsaeng decision, applying the “first sale” doctrine to copies of copyrighted work made abroad, strongly impacts companies with copyrights of luxury goods. A substantial amount of goods are imported into the United States each year. In the Kirtsaeng decision, Justice Breyer explains, “over $2.3 trillion worth of foreign goods were imported in 2011… [and] American retailers buy many of these goods after a first sale abroad.” To prevent importation of luxury goods without authorization, companies are heavily dependent upon asserting copyright protection. In a statement given by Ariel Lavinbuk of Robbins Russell, Counsel for amicus Costco, Inc., in support of Petitioner, explains further:

“The luxury-goods industry has an interesting relationship with copyright law. Whereas some segments of that industry – watches, for example – are able to avail themselves of copyright protection, other segments – such as fashion designs – typically have not. One effect of this dichotomy has been that certain types of luxury goods have had more weapons at their disposal to prevent parallel importation. The Kirtsaeng decision effectively ends that disparity.”

Lavinbuk emphasizes the importance of the Kirtsaeng decision. Now, companies can no longer depend on their copyrights to prevent importation of luxury goods without authorization. Instead, companies will have to adapt to the changes after Kirtsaeng.

Post-Kirtsaeng, companies will likely begin implementing a more standard international price to maintain a competitive edge. Lavinbuk commented on this prediction by saying:

“Now, neither watches nor fashion designs nor any other type of luxury good can use copyright law to enforce territorial price discrimination as between the U.S. and other countries.”

Agreeing with Lavinbuk, we see the benefits of the Kirtsaeng decision. Consumers of different countries can benefit from a common pricing standard. Comparatively, the companies producing luxury goods must also be considered. The luxury goods industry already has little copyright protection and has been forced to endure near exact replicas of its goods. Now with the Supreme Court Kirtsaeng decision, the fashion industry is faced with a slew of other issues.

Allowing the reselling of imported goods without authorization creates problems in brand protection, distribution and licensing. Luxury goods are likely to be sold below the standards that the original copyright owner would implement. Corporations may no longer be able to track where their copyrighted goods end up, which leads to the risk of brand dilution. Licensees carrying brands’ authentic products at a standard price are likely to be put out of business with redistributors buying goods from those who import from abroad and selling similar products at a lower price.

Many of these concerns Kirtsaeng raises were reflected in the Costco Wholesale decision. Omega was displeased that its luxury watches were sold at Costco. Having its watches sold at a wholesale store diluted the high-end brand. Omega was also unaware that Costco would end up with its watches, which created concern for Omega’s distribution lines. Lastly, Costco was not even a licensed retailer of Omega products, but a consumer could get authentic and cheaper Omega products at Costco. Now with the Kirtsaeng decision, the concerns of Costco Wholesale have resurfaced.

Due in part to concerns of luxury goods manufacturers, Congress may take action to protect manufacturers and overrule the Kirtsaeng decision. On March 21, 2013, Maria Pallante, the 12th U.S. Register of Copyrights, testified before the Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property and the Internet Committee on the Judiciary, for a substantial revision of the Copyright Act that is “more forward thinking and flexible.” She argued the current Copyright Act is dated and unclear, which creates difficulty for the courts. Many analysts support amendments, and predict they will take place soon with final revisions implemented by the end of four years. Considering the affects of the Kirtsaeng decision, we propose an amendment to be included in the probable revision to deter its negative effects.

Resellers of parallel import luxury goods should make royalty-like payments to the copyright owners. Royalties are usage-based payments made by the licensee to the licensor for the right to use an asset. The royalty amounts are typically an agreed upon percentage of the profit derived from the asset. The proposed solution is somewhat analogous to the process of library lending. Generally, libraries charge for borrowing a copy of a digital book. The reason for this charge is that the library has to pay the publisher for a license to use and distribute the book. Here, the reseller of the luxury goods will be paying the copyright owner for reselling its goods.

Royalties in lending books are different for obvious reasons. The most significant differences are that the luxury good is sold to the owner permanently and no licensee-licensor relationship exists between the seller and consumer. However, these differences should have no affect on the payments made to the copyright owner. The copyright owner’s energy and resources devoted to the copyright must be compensated, and royalty-like payments made to the copyright owner will offset the effects of the Kirtsaeng decision while encouraging the copyright owner to continue production.

A royalty-like payment would also keep the public interest at the forefront. If percentage based payments were implemented, it is less likely that the luxury good industry would pull out of the foreign market, where these items are manufactured at a lower cost. Goods manufactured cheaper should result in cheaper priced goods for the public. However, if the luxury goods industry pulls out of the foreign market that provides cheaper manufacturing costs, the result is likely to be higher priced goods, due to high production costs in the United States. The benefit of the goods being produced in the United States does not outweigh the manufacturing costs that could be saved overseas.

Resale royalties are already successful. Extending its application to the luxury goods industry would benefit the copyright owner and the public. Congress should amend the arcane and complex copyright rules accordingly. The result would be a more balanced approach towards production and resale of luxury goods.

Sources:

http://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/kirtsaeng-v-john-wiley-sons-inc/

http://www.copyright.gov/regstat/2013/regstat03202013.html

http://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/12pdf/11-697_d1o2.pdf

*Special Guest: Ashli Weiss, Fashion Law Society, UC Hastings School of Law